Fed begins quantitative tightening on unprecedented scale

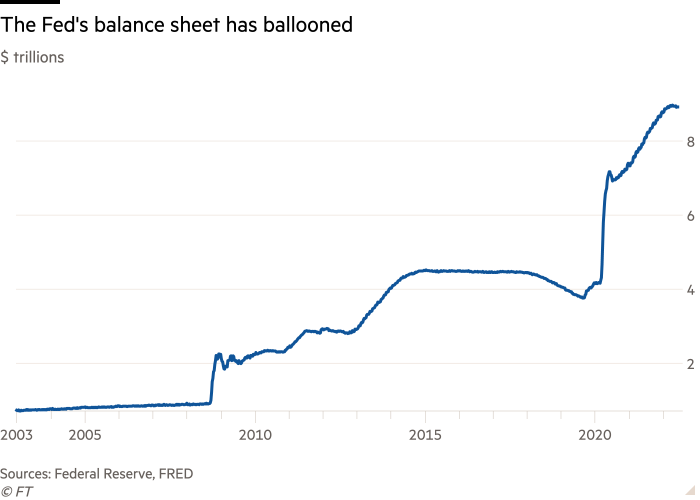

The mammoth task of shrinking the Federal Reserve’s $9tn balance sheet has finally begun.

On Wednesday, the US central bank will stop pumping the proceeds of an initial $15bn of maturing Treasuries back into the $23tn market for US government debt, the first time it has done so since it kicked off its bond-buying programme in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic.

While the Fed has flagged its plans for so-called quantitative tightening well in advance, investors are not clear what the impact will be of a process that has never been attempted at such scale before. The move could further unsettle a bond market already battered by speculation that the Fed is poised to accelerate the pace of its interest rate rises.

“The Fed has been a big buyer and a big stabilising influence in the markets for a couple of years,” said Rick Rieder, chief investment officer for fixed income at BlackRock.

“Losing that, with the uncertainty around inflation and growth, means that volatility in the rates market is going to be high, much higher than we witnessed over the last couple of years,” he added.

The unease in financial markets challenges the Fed’s assertion that balance sheet reduction will be a dull, predictable endeavour — likened to “watching paint dry” by former chair Janet Yellen the last time the central bank embarked on the exercise in 2017.

As was the case then, the Fed is allowing bonds to mature and will not reinvest the money, rather than selling them outright — a more aggressive alternative.

Members of the Federal Open Market Committee in May officially agreed to cap the run-off at an initial pace of $30bn a month for Treasuries and $17.5bn for agency mortgage-backed securities, before ramping up over three months to a maximum pace of $60bn and $35bn, respectively. That translates to as much as $95bn per month.

When the amount of maturing Treasuries falls below that threshold, the Fed will make up the difference by reducing its holdings of short-dated Treasury bills. Active sales of agency MBS may also eventually be considered.

That is a far more aggressive plan than the last balance sheet unwind in 2017-19, which began nearly two years after the Fed lifted interest rates for the first time since the global financial crisis. That move ultimately ended in disaster: overnight lending markets seized up, suggesting the Fed had pulled too much money out of the system.

As the process gets under way this time, it’s unclear exactly where the pain will be, although the Fed now has various emergency facilities in place that may help to stave off a repeat of the 2019 market mayhem.

Anticipation of higher interest rates — notably after two reports in recent days indicating a growing risk that inflation will become more deeply embedded — has driven yields on Treasury bonds to their highest levels since 2007. The three major US stock indices have fallen into correction territory. Spreads on US corporate bonds are showing higher chances of default.

Changes to the Fed’s main policy rate are seen as having a more direct impact on financial conditions and economic activity than quantitative tightening, but economists do expect balance sheet run-off to have an effect as well.

When the Fed buys bonds, it electronically credits the seller, in turn adding reserves to the banking system that then enable banks to increase their lending to individuals and companies. By ceasing to reinvest the proceeds of its bond portfolio, the process reverses, leading to fewer reserves in the system and tighter financial conditions.

In a paper published by the central bank earlier this month, researchers surmised that reducing the size of the balance sheet by roughly $2.5tn over the next few years is “roughly equivalent” to raising the federal funds rate by just over half a percentage point “on a sustained basis”. They caveated their findings with a disclosure, however, that the estimate is “associated with considerable uncertainty”.

Christopher Waller, a Fed governor, has previously said the central bank’s plan to shrink its balance sheet amounts to “a couple” of quarter-point rate rises, while vice-chair Lael Brainard said in April that the process in its totality could be worth “two or three additional rate hikes”.

Some analysts including Meghan Swiber at Bank of America and Edward Al-Hussainy at Columbia Threadneedle argue that the direct tightening effects of balance sheet normalisation described by top Fed officials have already been anticipated by the market and are reflected in asset prices.

But the Fed’s pullback is also likely to have a secondary effect on prices as liquidity — the ease with which investors can buy and sell assets — deteriorates as markets grapple with a larger amount of bond supply to absorb.

“Our understanding is that the Fed’s involvement in the market and buying Treasury securities helps improve liquidity, helps improve market functioning,” said Swiber. “And now we’re going to be in an environment where there’s more supply that needs to be taken down, and the Fed is not there to help.”

That means that the size and frequency of price swings may worsen as the Fed withdraws from the market, particularly in the Treasury market, where the central bank has had the biggest presence. But because the Treasury market is the backbone of all US financial markets, those effects ripple out.

Liquidity in the Treasury market in recent weeks has been at its worst levels since March 2020 in the days before the Fed was forced to intervene and buy bonds to ease market functioning, according to a Bloomberg index that measures traders’ ability to execute deals without affecting prices.

Get alerts on Monetary policy when a new story is published